“People are drawn to communities like this because they want to share things, and they want to be part of a community.” – Developer Carl Crave describes his Glencairn Cottage Court in Dunedin, FL which features a shared courtyard garden, rear-loading garages, and sits within walking distance of Downtown. The development was so successful he “built right through the recession, and not one owner has sold yet.” Shown above is a Glencairn cottage court under construction.

The Tampa Bay housing market is underserved in providing affordable housing options for residents, and that trend is expected to grow. According to the U.S. Census Bureau, the Tampa Bay region had the fourth highest population growth in the country for 2016. Additionally, 39 percent of Pinellas County households are considered cost-burdened by the Department of Housing and Urban Development, paying more than a third of household income for housing costs. This growing demand, paired with a limited supply of housing, has resulted in a steep rise in housing costs.

A possible solution may be to provide a greater variety of housing types that can accommodate more people without changing the character of existing neighborhoods. Blake Lyon, director of Pinellas County Development Review Services, says, “We have done a really great job providing single-family housing, and also denser multifamily buildings, but we have not traditionally provided housing types we associate going between the two, which is the Missing Middle.”

The Missing Middle is a term coined by urbanist and architect Daniel Parolek to describe multi-unit, low-rise housing comparable in scale to single-family homes. These are typically smaller residences with design elements that encourage walking, biking, and transit use. These housing types include a variety of styles, including shotgun and skinny homes, duplexes, triplexes, fourplexes, courtyard apartments, bungalow courts, townhomes, multiplexes, and live/work units.

A site plan of Glencairn. Source: Pocket Neighborhoods, Inc.

Several local communities have identified Missing Middle housing as a viable option to provide a wider selection of choices across many income levels because of its appeal to different types of home buyers, lower associated entry costs, and traditional architectural style. These features make Missing Middle housing ideal for first-time home buyers, smaller families, couples, retirees who desire to age in place, adults with disabilities, car-free households, and many others.

“The Missing Middle is an appropriate housing type for walkable, medium-to-high density communities, so we are looking at our code to identify locations adjacent to commercial corridors and transition zones in single-family neighborhoods,” says Derek Kilborn, manager of St. Petersburg’s urban planning and historic preservation division.

A History in Tampa Bay

A historic photo showing traditional casitas in Ybor City, Fla. Source: City of Tampa.

“Early in the infancy of Tampa, Ybor City provided the first type of affordable housing that had been realized, and that was in the form of the workers’ houses that surrounded factories,” says Dennis Fernandez, planning manager of Tampa’s Architecture Review and Historic Preservation programs.

In Ybor City, shotgun-style houses – narrow homes typically one room wide – known as casitas were built in the late nineteenth and early twentieth century as workers’ housing near cigar factories. Cigar factory owners would often subsidize housing in an attempt to lure workers to the area from Cuba and Key West to provide workers with affordable places to live within walking distance of their jobs.

Developer Michael Mincberg specializes in rehabilitating historic Ybor casitas and he believes this type of housing served a purpose in the past and serves a growing need in the future.

Sight Real Estate, led by developer Michael Mincberg, redevelops historic casita homes in the Ybor City area.

“The appeal of Ybor City is you’ve got a mix of uses abutting next to each other like single-family, multi-family, commercial, retail, office, and industrial,” he says. “That urban fabric is what draws people here; the ability to live, work, and play all in the same place.”

The legacy left in Ybor has inspired others to build this type of housing. Local developer John Bews recently completed Hayes Park Village, a walkable community comprised of detached skinny-home cottages in Oldsmar, Fla. He incorporated many of the historic features seen in communities like Ybor City because he believes they have a lot to offer.

“Cottages are small[er], maintenance was lower, and the cost of build was less, so by default they became more affordable,” Bews says.

Marie Dauphinais, planning director for the City of Oldsmar, says the city supported the development early on, and she helped Bews with the regulatory and permitting process.

Hayes Park Village in Oldsmar, FL features a community courtyard complete with a shared fire pit and open green space.

“It’s a unique development that benefits the city and the people that live there,” she says, and “it’s a very walkable community in close proximity to jobs, activity centers, schools, a park, and the trail system.”

In Pinellas County, the majority of Missing Middle housing types are located in historically denser neighborhoods like Dunedin, Gulfport, St. Petersburg, Clearwater, and Largo. Today, appropriate locations for Missing Middle housing include the perimeter of downtown areas or town centers; adjacent to commercial corridors; between single-family neighborhoods and denser multifamily areas; or on collector roadways that serve as borders between single-family neighborhoods.

A Planner’s Guide to Missing Middle Housing

The Missing Middle fits into existing neighborhoods exceptionally well because the size, scale and aesthetic are typically compatible with the surrounding housing types even though they have much higher densities than traditional single-family homes. Regulating these housing types can pose challenges, however, because they don’t fall into traditional zoning or land use categories. They are typically too dense for single-family neighborhood zoning districts, but not large enough in scale for multifamily zoning, where regulatory factors and the real estate market encourage larger and denser developments.

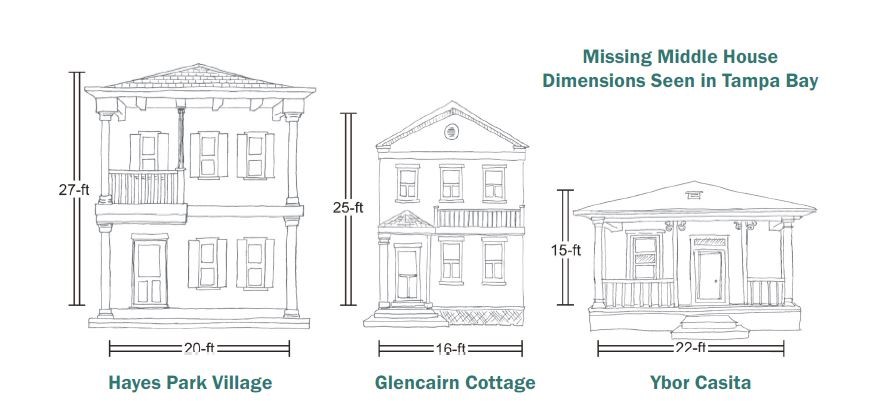

Three Missing Middle housing type examples seen in the Tampa Bay area. Drawings by Planner Susan Miller.

In addition, Missing Middle developments often include design characteristics like shared green spaces, courtyards, and rear-loading parking, which may not fit into a local government’s traditionally allowable uses. While some Missing Middle developments have been built in Pinellas County, each required a time-consuming, expensive process requiring many variances for setbacks, parking, utility easements, and other current zoning regulations.

Amending or rewriting zoning regulations to allow for higher densities, narrower lots, smaller setbacks, and higher floor area ratios help to encourage Missing Middle housing by eliminating the need for multiple variances, which can complicate the permitting process and discourage this type of development. Parking should be approached with flexibility, where opportunity for community interaction at street-level is the focal point and vehicle parking is less emphasized. Creative placement of utilities (including undergrounding utilities and stormwater vaults, and the addition of sustainable features such as reclaimed water and solar panels) is often required.

For these reasons, many cities use a form-based approach to preserve neighborhood characteristics when raising densities. Form-based codes become part of the guiding regulations by which developers have to abide, and are subject to design requirements such as building setbacks, widths and heights.

Above all, when Missing Middle housing types are not allowed by right, planners need to think creatively. Case studies in Pinellas County all exhibit a collaborative effort between planners and developers working within planning regulations at the local level to create aesthetically pleasing and walkable communities.

Forward Pinellas is currently looking at elements of the Countywide Plan to see how we can facilitate Missing Middle housing. Additionally, we are working on amendments to the Countywide Rules and evaluating the need for changes that could facilitate more Missing Middle housing opportunities in Pinellas County.

The Knowledge Exchange Series

In an effort to provide technical assistance relevant to the unique challenges of planning within a redeveloping Pinellas County, Forward Pinellas created the Knowledge Exchange Series (KES). An integral part of aligning land use and transportation planning is rooted in understanding the housing needs of the county and its relationship to how people move from place to place. Finding the Missing Middle, explores the gap in housing options in Pinellas County and provides guidance for local governments to fill that void. For more information, see the Knowledge Exchange Series page.

Mr. Blanton’s comments at Forward Pinellas were spot on. The nays to mass transit have circled around perceived lack of density (and funding methods). “Making” density of a helpful nature (1st non rental purchase by young technical and support workers and newly retired) that demands transportation support to get to the next node or area is an amazingly helpful old idea. The potential downside is also apparent (like residential Ybor City). All things age. The building parameters must specify construction that is of high enoigh quality to last and, after time, to invite rehabbing. One of the successful big examples of this is Morningside in Atlanta or, closer, Seminole Heights in Tampa.

What makes these small footprint houses work is the aversion to MacMansion grandiosity generally trending among Millimeals and the reversal of rhe post WW2 move to the suburbs. Outmovement from town centers seems to be playing out and the pendulum is swinging the other way.

Will you please provide housing for the high income disabled person’s.