If we’re going to adapt our land use and transportation planning to a new reality, we’re going to need to rethink access in Pinellas County and the Tampa Bay region. Our automobile-oriented culture is undergoing changes from demographics, market trends, technology and public preferences. Those changes favor seamless travel experiences that connect people to places where we have a variety of options for housing, how we socialize and how we reach our destinations. Prevailing socio-economic winds favor a highly mobile, well-connected knowledge-based workforce. We also have an aging population seeking to remain independent and active, with excellent access to health care, educational and cultural opportunities. Surveys show both populations want to live in accessible places with lower household and transportation costs.

SunRail is helping to expand those options in metro Orlando. That experience is instructive to the Tampa Bay Transportation Management Area Leadership Group’s consideration of whether to purchase the CSX rail tracks connecting Brooksville, Pasco County and Pinellas County with Hillsborough County. Here are a few takeaways from SunRail:

“One message, many voices”

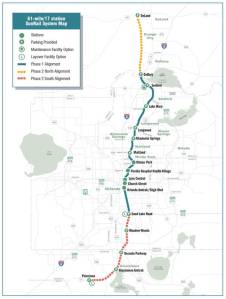

Getting the SunRail project funded and operational took great perseverance. After the Orange County Commission voted away federal money for light rail transit in 1999, the region re-grouped and came together for a 61-mile commuter rail line using existing CSX tracks. Over a dozen years, a committed, focused partnership of public agencies, regional institutions and key business leaders held firm on the project as the top regional transit priority. It held together through approval of inter-local agreements for governance of SunRail (creating the Central Florida Commuter Rail Commission), capital funding commitments and operations cost sharing. It took the leadership of the Florida Department of Transportation, Orlando Mayor Buddy Dyer and Orange County Mayor Teresa Jacobs, along with two MPOs (MetroPlan Orlando and Volusia County’s River to the Sea TPO), bipartisan Congressional support from Sen. Nelson, Rep. Mica and Rep. Brown, and numerous other government and business leaders stepping forward to show their commitment to SunRail. As SunRail manager Tawny Olore said, “If it takes a village to raise a child, it takes a community raise a train.” Her message regarding regional leadership: “One message, many voices.”

Multimodal access makes for a dynamic urban area

SunRail has introduced a new form of regional access to the metro Orlando region. Regional and local governments have worked in partnership to put plans in place that guide context-sensitive development and redevelopment, expand modal options, and help preserve existing neighborhoods facing rising land values and potential displacement. SunRail officials estimate there is $3.2 billion in economic development activities occurring around the operational SunRail stations. The Station House project in Lake Mary is a great example of a suburban Transit Oriented Development that came to fruition as a result of visionary local planning and the investment in rail. With mostly 1- and 2-bedroom units, it is marketed toward millennials who work in downtown Orlando or at hospitals and other employers along the line. Similarly, Juice Bikeshare started in downtown Orlando in 2014 and has expanded to Winter Park, helping to connect people using the train with nearby residences and destinations.

The line connecting Volusia, Orange and Osceola Counties is a long-awaited start. It began as a 2nd place consolation prize after Orange County passed on light rail, but it has become a catalyst for development of a comprehensive system connecting the region’s existing and emerging centers. In September, the Federal Transit Administration advanced a new line to Orlando International Airport, which connects to the All Aboard Florida high speed rail linking Orlando, West Palm Beach, Fort Lauderdale and Miami.

Failure makes you more determined for success

Houston’s MetroRail is one of the most successful passenger rail systems in the southern U.S., but it had 20 years of failure before building its rail lines, mostly with only local funds due to Congressional opposition. Orlando, like Houston and many metro areas, experienced many failed transit initiatives before finding success with SunRail. Dave Grovdahl, a former MetroPlan Orlando staff member, prepared this summary of 30+ years of newspaper headlines chronicling those mostly failed plans through 2007. A transportation sales tax referendum in Orange County failed in 2003, and Osceola County lost a sales tax vote in 2010. SunRail faced numerous deadlines and threats before finally gaining approval in 2011. Houston’s MetroRail and Orlando’s SunRail are evidence that building rail takes commitment and perseverance in the face of opposition at local, regional, state and federal levels.

Set the table for desired development

Neighborhood districts are thriving in metro Orlando and the Tampa Bay area. While many of these districts have evolved organically, they often result from a blend of community activism, thoughtful planning and significant public investment in streetscape, parks and transit facilities. Distinctive mixed-use destinations in St. Petersburg, Tarpon Springs, Safety Harbor, Dunedin and Gulfport all have benefitted from plans and development codes that nurture inviting, walkable places. They are critical to effective rail transit. As the City of Lake Mary’s community development director explained, “We set the regulatory table for transit-oriented development” with the city’s plan adopted well before SunRail.

The City of Altamonte Springs’ SunRail experience is instructive. Like Lake Mary, for most of the 1980s and ‘90s, Altamonte directed growth toward its Cranes Roost downtown redevelopment area in the I-4 corridor. When SunRail was conceived to run along the CSX tracks in the early 2000s, the station was one mile to the east in unincorporated Seminole County and many more miles from the City’s redevelopment vision. Having spent millions of dollars on Cranes Roost, the City had to adapt to the new reality, and responded by creating a bold plan for redevelopment near the SunRail station. The plan included acquiring land for a community stormwater facility that enables higher density mixed use development within the city limits. Seminole County worked with East Altamonte residents to craft a community-based plan that protects its historical and cultural identity.

In a highly connected world, we need to think both big and small. We need to think big by envisioning better ways to grow our economy and communities with transportation in all its forms, and with more diverse and mixed land use and housing strategies that are fiscally, environmentally and socially sustainable. Is CSX that opportunity? We need to think small by recognizing that character of place – our sense of connectedness – is increasingly the driver of personal and corporate location decisions. Is Oldsmar that place? Can it be? For any decision, we need to be mindful of the character, culture, history and pride of ownership each community values. We need to carefully assess how any investment supports our least advantaged and struggling residents, while providing benefits broadly to the county and region.

An investment in rail and other forms of premium transit can be a critical catalyst toward strengthening and revitalizing our core areas that have long struggled for that kind of attention and economic opportunity. As with Orlando’s experience, we need to recognize this is a team marathon, not an individual sprint.

While it’s nice to throw around “Feel Good” numbers all is not the bed of roses. First off John Mica and son’s saying that Orlando International Airport should connect up with SunRail is a given. Okay, who doesn’t know that? He got his sound bite and video out there. But then…”yeah I know there’s no money for this” even 5 years down the road. And what good would it do to have a airport connector when the train stops running at 10pm? Weekends? Gee John no money for that either. Then he takes it upon himself to “announce” that Florida East Coast Railway (FEC) and All Aboard Florida (AAF) want/need a Daytona Beach stop. Except it was news to AAF. Then he spits out that well you know the whole Deland extension? I just don’t see no future money for that. That blindsided Volusia County officials who thought that once the SunRail line was extended into Deland it made perfect sense to extend it into Daytona Beach. But not Magical Dreams John Mica..He doesn’t seem to understand that in 6 years FDOT Funding of SuRail ends. In its first year of operation on it’s very limited track now it ran a 27 million defict. After it’s expanded into Osceola County will it’s increased ridership of another dollar per new passenger going to cover the Train’s new expenses? Of course not. No public transportation system pay’s for itself or makes a profit. So how does John Mica think that SunRail will be able to afford to build a dedicated OIA train loop and then run it to? Guess all that Free Maglev Train bit the dust and even in its first pixie dust presentation didn’t have a SunRail stop. If John Mica had any visionary dreams it would be how to expand SunRail to the towns of Apopka, Zellwood, Mt. Dora, Tavares and Eustis along the Florida Central Railroad tracks which also parallel US 441. These tracks terminate in Downtown Orlando at Robinson St a mere blocks away from Lynx Central Station. Imagine that? But at this point that too is nothing but wishful thinking. Florida Central track’s are not rated for commuter rail and to upgrade everything would be close to a Billion dollars. Ol Smiling lying threw his teeth Buddy Dyer sold everyone on this Train. Right now he along with other Mayor’s ain’t worried about how to pay for the Train. In fact ol Buddy who’s newly elected term will expire in 2020 could just simply say “You know, I’ve been your mayor for 20 years now. I’ve decided that’s enough”. Come 2021 the train falls into 4 local counties in how to pay for it. One scheme already shot down by the Florida Legislators was to tax rental car’s. They don’t have a plan “B” right now. Please don’t misunderstand me. I’m all for rail. I ride Amtrak when I can. SunRail? Not do much cause it doesn’t go where I need it or late enough or weekends…. And now the City is obligated to pay for operating deficits to the Performing Art’s Center. This white elephant will never pay for itself either. Ask Miami… Good luck folks.. A government official with a “vision” has his hands in your wallet…